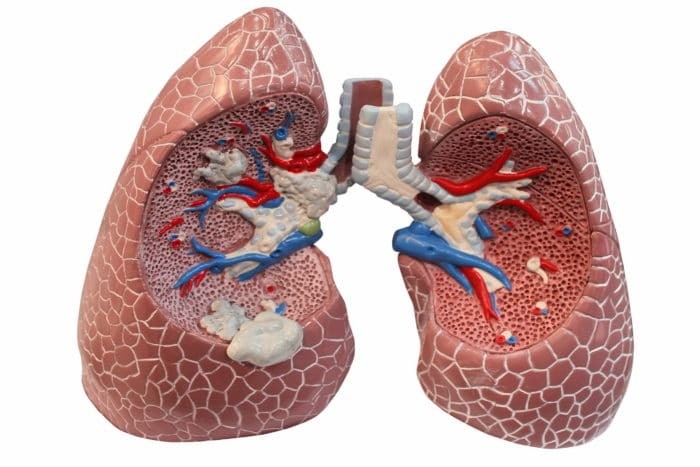

Lung barotrauma, or what members of the freediving community commonly refer to as “lung squeeze,” is an injury to the lungs caused by rapid changes in lung pressure related to the surrounding pressure at depth. Lung squeeze can present as pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, and possibly arterial gas emboli (AGE).

Freedivers enter into lung squeeze territory typically after they reach the RV (residual volume) threshold of the lungs, typically beginning between 30-40m (98-131ft), or even shallower in some individuals who are not flexible in their chests. Since air volume is not able to decrease past this point, intrathoracic (chest cavity) pressure decreases, which results in the feeling of negative pressure in a freediver’s chest. Diving past this point increases the chances of a lung squeeze. So how can freedivers prevent lung injuries once they reach deeper depths?

Flexibility

Chest and diaphragm flexibility is fundamental for freedivers once they reach their lungs’ residual volume. This is why, in most freediving courses, diaphragm stretches like uddiyana band and chest stretches are taught when students are reaching around 30m (98ft) of depth. The more flexibility the diaphragm has to move upwards, filling the empty space that the lungs leave when they shrink in size, the less pressure a freediver feels, and the more protection the lungs have against lung squeezes. Training flexibility on dry land is highly recommended before even reaching these depths so that a freediver bypasses the feeling of negative pressure in the chest and can continue their depth training without interruption due to an increase of chest flexibility.

Good Posture

Posture is not only important for efficient, hydrodynamic technique and a more relaxed freefall, it is also important to protect against squeezing. Some athletes are able to maintain a completely straight posture while freediving, but these are highly trained and flexible athletes, not the typical recreational freediver. This means that when a freediver is descending and ascending, their chin should be slightly tucked, slightly rounded shoulders, a relaxed belly, and legs marginally bent at the hips and knees, so as to remove tension from every part of the body and aid in relaxation.

Efficient Turn

The turn is a crucial part of a dive, as it occurs at the deepest point of the dive where you will feel the greatest amount of pressure. This is where some freedivers may make the mistake of extending the neck and opening their chests in order to see where the end of the line is. This already may indicate nervousness and an absence of relaxation and creates tension in the body, which can be accompanied by trachea or lung squeeze. Turning like a skydiver, with an open chest, is also dangerous, which is why it is important to practice the forward-tumble turn from an early stage in your freediving career in order to create good habits. Ascending from the turn is also the place where you should make shorter pulls while doing free immersion, or avoid putting your arms over your head in constant weight, at least for 10m (32ft) or so, to avoid opening your chest with so much pressure on it.

Jerky Movements

Having strong contractions or struggling too hard to fix your freefall can have consequences when you have reached your lungs’ residual volume. Even getting frightened or surprised at something during the dive, losing the line and struggling to look for it, or jerking your arm out and making a rapid turn may have consequences for the delicate tissues of your lungs. Every movement and reaction should have a precise and controlled movement attached to it, and surprises or excitement at depth should be avoided.

Staying Relaxed

The longer the dive and the greater the surrounding pressure, the more difficult it can feel to stay completely relaxed. Relaxation is essential in freediving, especially at deep depths, as it keeps our chests flexible, aids in equalization, and keeps us from burning through our oxygen stores quicker. If you are holding tension in your core, or are starting to get nervous or anxious, you are more likely to make a wrong move that will result in an injury. If you recognize this in the middle of a dive, make a slow turn and come back to the surface; if you are feeling anxious and cannot relax before a dive, then it is better for your mental state and for your safety to not perform the dive at all.

Slow Progression

Reaching a new PB (personal best) is an exciting rush, and can be addicting. Forgoing safety for higher numbers on your dive computer, on the other hand, can be dangerous. Our bodies need to adapt to depth before going deeper. This means that once you reach a new personal best, stay there for a bit; make multiple dives to that depth, and when it feels comfortable, increase 1-2m (3-6ft) rather than making big leaps of 4-5m (13-16ft) or making one PB dive right after another. Make sure to do proper warm-up dives before a deep dive in order to put your body in “freediving mode” and to encourage a strong blood shift.

Final Thoughts

Our lungs are our most precious asset in freediving; more attention and care needs to be paid to them when achieving certain depths and beyond. Self-awareness and listening to our bodies are essential parts of freediving and can make all the difference between a safe freediver and an unsafe one.