I recently watched the video of Tanya Streeter’s 2002 record breaking 160m freedive. I saw her slide down into the deep in her brave silver fish suit. I saw her at the bottom when narked more than she knew she blew a kiss to the camera and failed to pull the pin on the air bag that would take her home.

I witnessed her quick confusion, her sudden realization, her fumble for the pin. I realized I was holding my breath too. I ached with fear. She found the pin, pulled it, I breathed again at her whirling ascent.

I wondered what made her do this thing, to come so close to dying.

This article is not about how dangerous an activity is; freediving is statistically no more and no less dangerous than many other extreme sports. We will all die, that is a given, and for all those who do things others don’t understand the hope is “but not today!”

Instead, this is about what compels people to test themselves to this extreme. To go deep into the dark, for no apparent reward other than knowing they did it. (I doubt freediving has many millionaires, so money isn’t a motive here, unlike say, for example, Formula One.)

What allows those who go to the deep to do something that must cause such fear in those that love them? Are they selfish, are they arrogant, or are they immune to fear?

On reflection, I realize those are the wrong questions.

Our man, Stephan Whelan, the DeeperBlue.com founder, pointed out in an interview with the BBC in 2015 that:

“Freedivers go to incredible depths, they do incredible distances underwater, they hold their breath for seemingly inhuman amounts of time, but freediving is a very peaceful and relaxing sport. If you watch freedivers before they go under, it’s about deep breathing. It’s about getting into a calm mental state and staying calm throughout the dive. And it’s a very introspective sport, the divers have to shut out the outside world. It’s a sport of two extremes – you go to extreme depths but you also have to go deep into yourself to do it.”

This perspective allows me to look again at the questions and formulate better ones.

A Switch in Perspective

We all have our own kind of normal.

It was shortly after my father died. My mother needed a holiday, she wanted me to go with her. “Great,” I said, “I’ll bring my kit; I can do some dives at the new marine park.”

“No,” she snapped, “I’m not taking responsibility for you.”

To me that was a bizarre thing to say. She doesn’t need to take responsibility for me – not least because I am 50! – I take responsibility for me. I know I am safe in my choices in the sea. But she didn’t appreciate that, she was horrified that I wanted to dive. I craved the quiet of the sea where grief is often washed away and she only saw the possibility of losing another to the dark.

We all fear what we do not understand.

I fear for Tanya Streeter because I am a mother, a daughter, an empathic re-runner of loss. But that is her normal, her dives were not death wishes, they were life affirmations.

Their families may fear for the extreme athletes but as mothers, wives, anyone who cares, in reality, we fear anyway, no matter what they do.

Many sports and pastimes are considered extreme at their inception, recreational car driving, the riding of bicycles, and scuba diving were all considered extreme occupations in the past. Scuba diving has moderated its image over recent decades due to the huge uptake in recreational diving although all of us have, at one time or another, been told by friends/relatives/acquaintances that they could never do what we do.

In 1999 Nevo and Breitstein published the volume “Psychological and Behavioral Aspects of Diving” which collected their most important researches. From their studies it appeared that, in comparison with the general population who do not practice this sport, the diver has more taste for risk and adventure. Those who don’t dive would definitely agree with that, those who dive may preen a little and modestly demur!

Those on the outside of an activity looking in are often confounded as to why participants do what they do. Freediving, or any journey into the dark depths of the ocean, is viewed as taking an unnecessary risk, particularly as the benefits and rewards are either so personal or so poorly understood that the most obvious thing is the danger.

Full Metal Jacket

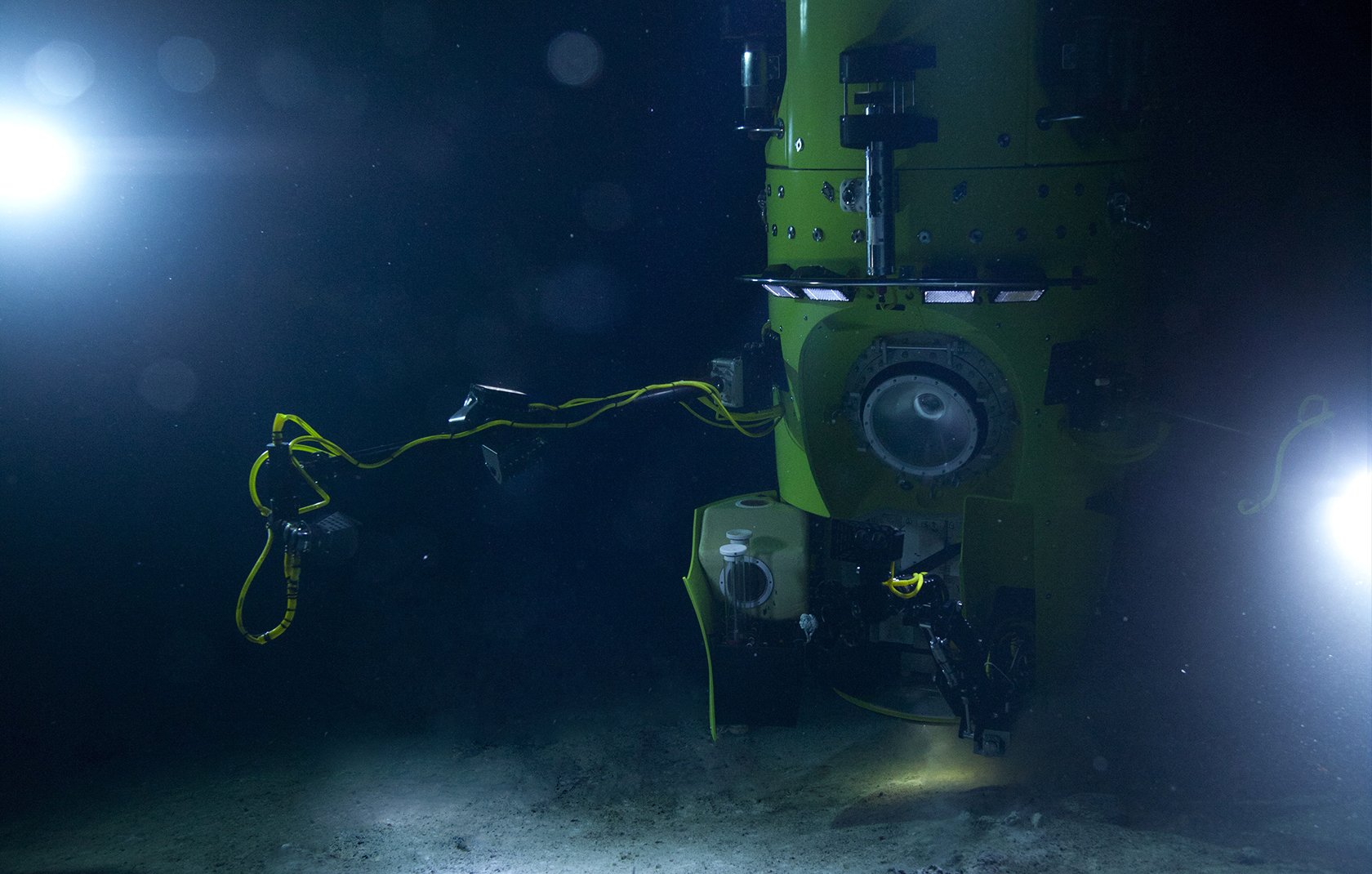

Freedivers go into the deep for themselves; aquanauts go into the deep for all of us.

Dr Jon Copley, a senior lecturer in marine ecology at the University of Southampton and the first British aquanaut to dive to a depth of five kilometers, writing in The Guardian following his submarine journey to explore hydrothermal vents said,

“The motives that spur our further journeys into the deep ocean will define its future. We can go there to learn from it, or to exploit its natural resources for our rapidly expanding population. Or perhaps for once we might achieve a balance between the two. The challenge of the deep ocean is no longer technological; now it is a test of whether our wisdom can match our ingenuity.”

Few have dived to five kilometres, but that is still less than halfway to the deepest spot on the planet, the Marianas Trench. The Marianas Trench in the western Pacific bottoms out at 11 kilometres. In 1960 Swiss engineer Jacques Piccard and US naval captain Don Walsh spent 20 minutes there, in the dark. In 2012 James Cameron, film director and undersea explorer spent nearly three hours at the bottom as part of the DeepSea Challenger Expedition.

Patricia Fryer, expedition member and marine geologist at Hawai’i Institute of Geophysics & Planetology told National Geographic News at the time that Cameron’s journey to the depths was more useful scientifically than unmanned missions.

“The critical thing is to be able to take the human mind down into that environment,” she told National Geographic at the time, “To be able to turn your head and look around to see what the relationships are between organisms in a community and to see how they’re behaving – to turn off all the lights and just sit there and watch and not frighten the animals, so that they behave normally.”

Another expedition member said:

“He’s down there on behalf of everybody else on this planet. There are seven billion people who can’t go, and he can. And he’s aware of that.”

Cameron himself said of the experience,

“It’s really the sense of isolation, more than anything, realizing how tiny you are down in this big vast black unknown and unexplored place.”

It is almost the default position to view such activities as pointlessly dangerous activities undertaken by loonies. However, psychological research indicates that a gung ho attitude to danger is an unlikely motivation for those who travel to the deeps whether under their own steam or via machine.

Addicted To Life

In 2009 researchers Erik Brymer and Lindsay Oades conducted a small-scale interview study of participants in B.A.S.E. jumping, big wave surfing, extreme skiing, waterfall kayaking, extreme mountaineering, and solo rope-free climbing (Brymer & Oades, 2009. Extreme sports: A positive transformation in courage and humility – Journal of Humanistic Psychology 49). The study explored the attitude of extreme sports participants to the psychological constructs of courage and humility. One of their main findings was that extreme sports participants felt their sports brought about a personal transformations that in a positive way spilt over into other areas in their lives.

This brings us back again to the personal experiences of freedivers and aquanauts. They all appear to feel transformed by their experiences, either calmer or humbler or more in control.

Our brains come pre-loaded with mechanisms that are designed to help us to avoid danger, but interestingly we are also equipped with reward mechanisms that are activated when we survive extreme experiences. Deep within the brain, in response to these situations, there are triggers that release dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that helps control the brain’s reward and pleasure centers. It also helps regulate movement and emotional responses, but most interestingly of all it enables us not only to see rewards, but to take action to move toward them.

I am reminded of an instance from my childhood. I am very young, and I am on the highest bar of the climbing frame, the ground a dizzying depth beneath me. “Watch me Dad,” I shout. He claps in admiration, my mother yelps with fear, and the dopamine rushes. I feel daring and unique. This is where we start to learn to love trying, with the first rush of reward.

Dopamine, as the hormone most linked to drug experiences, is a learned response. The brain can’t tell the difference between the degrees of danger involved in the activity being performed, it just notes that the activity resulted in the activation of the brain´s reward system, and it liked it!

Finding Your Zone

Tanya Streeter may not currently be attempting to break world records but she is still a freediver – as she said in her most recent interview with Overview Effect website

“If you’re underwater holding your breath, you are freediving. From there you can see that it’s a sport for pretty much anyone. But it IS more than a sport. It’s an exploration of oneself, if indeed you do decide to see how deep or for how long you can dive.”

I don’t think there is madness in the deep dives, there isn’t recklessness and there isn’t necessarily adrenaline, in fact in some instances adrenaline would be dangerous and counterproductive. I think going into the deep is about finding your zone, your place, and for free divers and aquanauts, it is in the ocean and who is anyone to question that.