The most successful World Record event is one which ends in failure.

It’s a variant of the Peter Principle, and makes perfect sense if one imagines an event with no scheduled Last Day: you just drop the plate a meter or three each day until your divers simply can’t do it anymore. The event is over when everybody’s blacking out, and it’s successful if yesterday’s dives made new records. With this paradigm clearly in mind, it’s easy to see that stirring a predetermined endpoint into the mix adds a strategic constraint to the game, felt as temptation by coaches, urgency by the divers and manifested in early-game failed dives.

Failed record attempts are perfectly okay when they happen as the last note in the tune when the song has already been played, records set, the audience is on its feet and the athlete is going for gravy. It’s the expected result of pushing beyond the new definition of human limits. That’s how come they’re World Records, after all.

The trouble starts when a sour note is played in the middle of the concert or worse, at the beginning. That’s when things can start to unravel. One the one hand there’s the Golden Way- nothing succeeds like success- but the flip side of that particular coin is a devil’s cloven hoof.

Mandy-Rae and the Devil

So the devil stepped on Mandy-Rae Cruickshank, and she didn’t reclaim the women’s World Record for the Constant Ballast discipline. Everything seemed to be in place to make it happen. She’s arguably in the best physical shape of her life and the living conditions for the athletes were, thanks to ICU Medical’s sponsorhip, the best ever. Which is to say the least burdensome on the competitors, although of the three Team athletes Mandy was the only one with a considerable administrative and logistical obligation to meet during the event.

The strange thing was that she never seemed as though she’d not do what she’d set out to do. There were setbacks as the competition days drew near, to be sure, but taken singly these things seemed trivial. Immediately after one aborted dive, for example, she reported what sounded to me like hypocapnia during the early stages of her descent. Indeed, I’d followed her with my video camera, and in the first few seconds of the dive had stopped kicking and flared my fins, concerned I’d overtake and bump into her for a DQ. And my head handed to me.

Was she goofy and slow? If so, it wasn’t for long. My camera was on a 15-meter cable carrying live feed to the surface, and when it jerked me to a stop my computer time was right where it should be. Big deal.

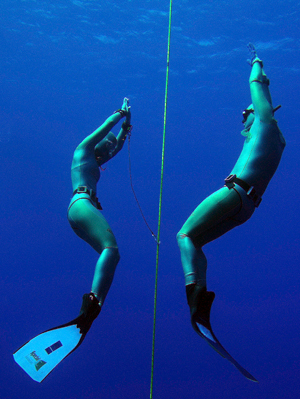

Breathing up again topside, waiting to drop and shoot her final approach and surface recovery I thought she looked very strong and clean as she came into visual range about 30 meters down. And indeed she was, powering up with her characteristic ballet-like grace. Still the synchronized swimmer from back in the day.

It looked like a win until about 3 meters left to go. It was as if somebody or something had simply flicked her OFF switch. The safeties had her mouth clamped shut and rocketed her to the surface in seconds. Holding her supine in the water, mask off, blowing gently on her face– her eyes were closed, her face slack. Mandy-Rae’s blackouts are hard for me to take. They scare me, for no good reason since her wake-ups are forceful and once begun, quickly completed. This time, she transitioned from a cadaver-like stasis to convivial normalcy in a second and said, matter-of-factly: “I dreamed I finished the dive.”

A well-trained athlete’s visualization playing out while her body has full-stopped ? Maybe, could be. But this time it never added up for Mandy-Rae. She went to Grand Cayman with a year of preparation and training invested in reclaiming her World Record, but did not.

Has Mandy-Rae Cruickshank finally reached her limit ?

Possibly. However, this reporter surmises that if this is the case, the limit is not being set by her athletic potential but, rather, by circumstantial constraints on her realizing that potential. Mandy-Rae’s chief rival for the women’s crown (Natalia Molchanova, Russia) enjoys the considerable advantage of year-round institutional support for her freediving, and makes her living in the water. Mandy makes hers mostly in the office. We’ll see.

Martin and his Mask

Martin Stepanek, now with his reclaimed Free Immersion (106m) and Constant Ballast (108m) World Records, has never blacked out freediving. What to make of that? Rare, almost unique among the sport’s keener enthusiasts of all ranks. I like to needle him about it (“You’re just not trying very hard, pal…”) but do so as another one who’s never blacked out freediving. I’ve blacked out jumping out of my recliner to run to the fridge during a television advert, but never in the water and never, ever on a Sunday. Since my freediving personal bests are not quite equal to Martin’s warm-ups, the shared trait here ain’t a physical one.

This isn’t to say that Martin doesn’t do bum dives. He does. His Sink Faze 2006 Constant Ballast attempt on 110 meters was a rather dramatic failure, just the sort of thing our growing audience of general-interest sports fans secretly craves when they watch auto races or boxing matches.

From my point of view in the water as a freediver with a video camera it started out with what seemed to me a triumphalist flourish: Caesar riding out to inspect his empire. I followed him down the line to about 30 meters, watching him through the viewfinder, and even allowing that a certain amount of my energy was invested in keeping him framed properly it seemed to me that boy was whaling. All power, streamlining and fluidity. I turned and broke the surface at 1’35” into his dive and started breathing up to go back down and parallel his ascent alongside the two safety freedivers. Kirk Krack and Tom Lightfoot dropped down at about 2’30” into the dive and were visible from the surface as they took up stations at 35-40 meters, waiting for Martin. Martin was already up to 55 meters, so they saw it coming.

I’d planned to time my own re-descent so as to meet the ascending trio at about 20 meters, thus to capture the passage through the blackout zone and the critical sixty seconds after breaking the surface. This time, I screwed up. I was a little winded from the follow-shot I’d done of Martin’s descent, and so when I noticed Kirk and Tom suddenly wiggling around down at 30 meters, I didn’t do what I should have done – I should have headed down immediately with camera rolling. Something was up.

Martin’s arms were down by his sides when his form emerged from the deeper blue. I was on my way, and saw the rest through the viewfinder. He was still moving up, monofin barely waving, Tom and Kirk close, close in on either side. Martin’s head went back – he looked up to the surface. That’s it, I thought. It’s all over. Tom and Kirk laid hands on Martin and started kicking toward the surface. I flipped and started up with them at about 10 meters, noting that neither safety freediver was holding Martin’s mouth shut – he was fully conscious. He’d not required rescue, he’d simply opted out of the wear and tear of a dive he’d already written off.

On the surface, Martin grabbed the float and removed his mask. Kirk and Tom backed away. Martin spoke immediately, and coherently. There was nothing of a hypoxic incident of any kind, but neither was there love. His terse, monotonic account of a totally flooded mask and a bailout 4 meters shy of the plate reminded one of a busy pathologist dictating the last biopsy report of the shift.

Odd, I thought. Very similar to what he’d reported after the dive before this one, the successful 108m performance with partial mask flooding. He’d said it was time to retire that mask and commission a new one. Why hadn’t he? Had this whole day’s platoon-size operation tripped over a $50 piece of gear?

I don’t think so. Backing off a little, it’s worth remembering that only a few short years ago many people thought any progress beyond 90 or so meters would be possible only without a mask. Martin was, himself, invested in R&D and use of fluid goggles back then. It seems more likely to me that at the depths he’s now reaching he’s passing through a pressure threshold beyond which the tiny incremental deformation of his mask and/or his face are breaking the seal and letting water in. Even for Martin Stepanek, the air in his lungs is in finite supply and some of it has to be allocated for the mask. If there’s not enough, there’s not enough.

Doc the CEO

Doc Lopez is in a class by himself. As he himself freely and cheerfully concedes, his own dives shouldn’t even be happening. “My sport is ice hockey!” he reminds us, and if pressed will own up to an earlier incarnation as a boxer. The guy is built like a rhino, a design suited to high kinetic aggression against other similar beings. He plays ice hockey eleven months out of the year, knocking the socks off his (former NHL pros!) buddies and then goes and freedives for a month.

He’s also 58 years old. “I think the best I could do in static apnea is maybe three and a half minutes.”, he confides. This from a guy who’d just done a 2’40” free immersion to over 50 meters’ depth. “I’m just an average guy”, Doc posits. .”All I’ve got going for me is technique. I find ways to do these dives with what I’ve got.”

So Doc has a lot on his plate when he’s diving. He’s tapped Herbert Nitsch for technical capital in the form of the feet-down posture for free immersion. Doc has 8 lbs. of weight stuffed into his socks when he does these dives– one can be certain this load was meticulously calculated. He’s focused on hydrodynamics going down, his pointed toes forming a penetrator of a leading edge and his elevated head minimizing the equalization budget. Doc is very much the CEO running his body and his dive as he would a company: cost-efficiently. When it doesn’t work, he’s reminded that Diving Doc is self-employed. A team of one, running a program with multiple foci in unforgiving real time.

Doc’s failed dives were, then, technical failures. Operational failures. His presentation when he surfaces seems shaky until one gets accustomed to it and learns that it’s about the same whether he’s done a warmup to 10 meters or a record attempt to 54. It’s the appearance of a man whose brain is trying to emulate an executive committee, multitasking an intimidating set of technical variables with an internalized AIDA compliance officer reading code and statute from the bench. So, when he screws up and does something like touch the float rig before his airway clears the water– well, it’s the kind of thing a guy can live with. It has a solution, a plain one, and the team inside will get the memo. No tears.

Keeping Up

Which isn’t to say that people come out of world record freediving events the way they went in.

The last weeks of the event cycle, which for top-shelf competitors runs several times a year, are physically exhausting. Deep apnea diving really takes it out of a body, and until freediving grows to the point where competitors are living like their counterparts in Big Sports, there’s going to be a lot of background noise for them to contend with as well. The same goes for the folks around the athletes. Everybody works hard, sleeps little, and the comforts are few. From my own limited experience of life, I’d say it’s like a cross between a theatrical production and military reserve duty. A tight, closed society is formed overnight and coheres as the days go by, soon doing the job as a well-oiled machine but oh! … the little frictions, inevitable where diverse humans interact, must be shunted aside to get the job done and so grow like weeds behind the woodshed.

A play has a director, and a military unit a commander. The skipper, the boss, the Chief. Kirk Krack is the man who made this most recent freediving World Records event happen and is the man ultimately responsible for every outcome, large and small.

As a media guy, I suppose I was at the very bottom of the command structure– what’s now called an “embedded journalist”, sleeping and eating with the troops and going where they go. From my vantage point Mr. Krack has done again what any true entrepreneur does best: growing his world and making it work on the edge of chaos, where the doors are blown out on a short fuse. The high-risk, high-reward play. It ain’t easy for his troops, but they keep coming back for more. Has any individual done more for the sport of freediving ?

Me, I’m just a scribbler who sleeps on a patch of kitchen floor by the garbage bin, which being the most public of places kept me up until last and awake with the first. Saw it all. I left the morning after the wrap party, the day after the last attempts when Doc and Martin failed and Mandy didn’t try. It’s only an hour’s flight from Grand Cayman to my home town in Florida, so by that afternoon I was wallowing in the comparative luxury of my own kingdom, mulling over the creativity reactor that was Sink Faze 2006 and waiting for Lessons Learned to form in my noggin. The PFI folks get no rest. Forty-eight hours after Doc’s final, frustrated attempt on 54 meters free immersion the team was on its feet teaching a 4-day clinic with 26 students, this to be followed by an invitational competition. Yipes.

The Lessons Learned agenda has a particular urgency this time around. Doc Lopez has thrown down the gauntlet, and I’ve accepted his challenge. Next year, we go head-to-head, mano-a-mano on Grand Cayman Island. The Geezer Freediving Open, don’t trust anybody under fifty. Something like that.

I’d better infringe all of Doc’s technique patents, and soon. He’s a much better athlete than I am, so I’ll have to get a leg up on some cool tricks. Fortunately, Doc’s agreed to tell all, and to the entire DeeperBlue.net readership, in an upcoming feature article.

Did I say something about ending in failure? To hell with bookending this article. Okay, some dives didn’t work out but others did, and big time. When the flight recorder data gets analyzed we’ll all know lots more about freediving than we did before.

And that, fellow divers, colleagues and only friends, is all she wrote.

There’s More!

Read more Daily Updates from Paul in our Sink Faze 2006 Special Feature Series and check out the Photo Gallery. Video and daily team updates at the Sink Faze website.