For centuries, vast areas of the ocean would glow steadily at night, even for months on end, a phenomenon dubbed “milky seas.”

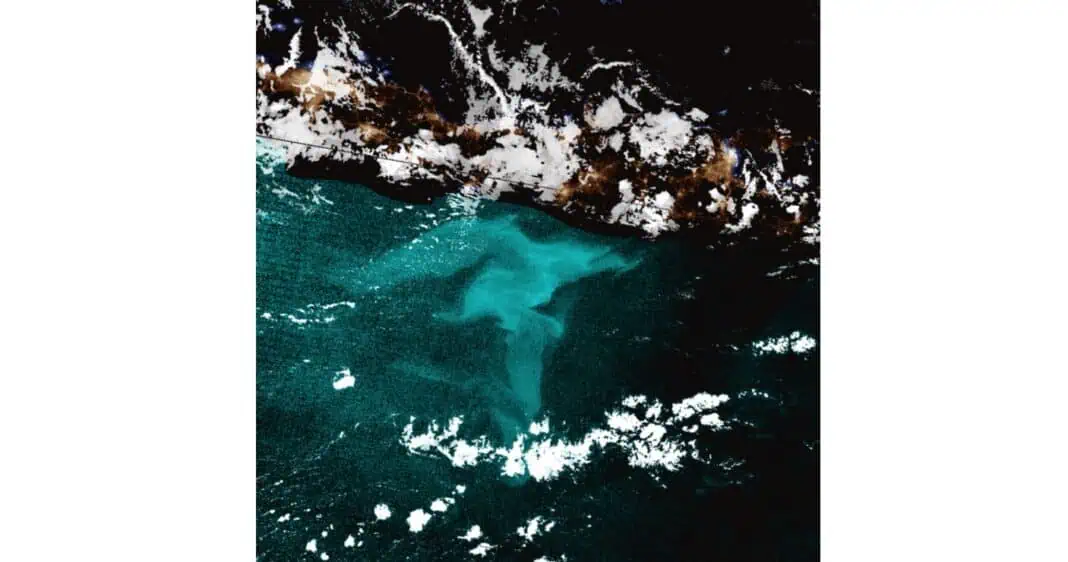

The light is bright enough to read by and is oddly similar to the green and white aura cast by glow-in-the dark stars that have decorated children’s rooms. Stretching over ocean space as broad as 40,000 square miles (103,600 square kilometers), the light can, at times, even be seen from space.

Sailors coined this rare bioluminescent display “milky seas.” Despite being encountered for centuries, scientists still don’t know much about what causes this glowing effect because they are quite rare – and they usually occur in the remote regions of the Indian Ocean, far from human eyes. A likely theory is that the glow comes from activity by a luminous microscopic bacteria called Vibrio harveyi.

To better predict when and where milky seas will occur, researchers at Colorado State University and the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere have compiled a database of sightings over the last 400 years.

Described in the journal “Earth and Space Science,” the archive includes eyewitness reports from sailors, individual accounts submitted to the Marine Observer Journal over an 80-year period, and contemporary satellite data. This is the first such collection of data on milky seas in 30 years. Together, it shows that sightings usually happen around the Arabian Sea and Southeast Asian waters and are statistically related to the Indian Ocean Dipole and the El Niño Southern Oscillation.

Justin Hudson, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Atmospheric Science and the paper’s first author, said the database will help researchers better anticipate when and where a milky sea will occur. The goal, he said, is to get a research vessel out to the site in time to collect information about the biology and chemistry within a milky sea. Information about those variables could be helpful to connecting the event to broader Earth systems activity.

Hudson added that the regions where milky seas occur feature a lot of biological diversity and are important economically to fishing operations:

“It is really hard to study something if you have no data about it. To this point, there is only one known photograph at sea level that came from a chance encounter by a yacht in 2019. So, there is a lot left to learn about how and why this happens and what the impacts are to those areas that experience this.”

Check out the full study in the journal Earth and Space Science.