On the morning of July 12, 1952, Forges Chantiers de la Gironde launched the last of four sister ships in Bordeaux, France, under the name of Jean Laborde. The ship underwent several name changes, including Mykinai, Ancona, Eastern Princess, and finally, in 1976, under the ownership of Pontos Nav SA, she was registered in Piraeus, Greece, under the name of SS Oceanos.

Originally built as a passenger/cargo vessel, the Oceanos underwent massive reconstruction by the time she came to operate as a cruise liner for Epirotiki Lines of Greece. The success of the 1988 cruise season in South Africa was the motivation for her return in 1991 on an eight-month charter for TFC Tours of Johannesburg.

En route to Durban, the Oceanos cruise ship set out from the port of East London on Saturday, August 3, 1991, into 40-knot winds and nine-meter swells. It has been reported that the ship was in a state of neglected maintenance with loose hull plates and an unfitted ventilation pipe. It had also had several sewerage-holding tank non-return valves stripped for repairs following problems with bilge water rising through showers and toilets on a recent trip to Mozambique. The unfitted ventilation pipe was said to have left a 10cm hole in the watertight bulkhead between the generator and the sewerage tank.

Why did the Oceanos sink?

Reports indicate that at around 21:30 off the Wild Coast of the Transkei, the Oceanus Cruise ship lost its power following an explosion in the engine room. The ship’s engineer reported to Captain Yiannis Avranias that water was entering the hull and flooding the generator room. The generators had been shorted, and the supply of power to the engines had been severed.

The water steadily rose and flowed through the 10 cm hole in the bulkhead and into the waste disposal tank. Without valves to close on the holding tank, the water coursed through the main drainage pipes and rose like a tide within the ship, spilling out of every shower, toilet, and waste disposal unit connected to the system. There was no stopping the flooding and no hope for the Oceanos sinking.

Realizing the ship’s fate, the crew fled in panic, neglecting to close the lower deck portholes, which is standard policy during emergency procedures. Passengers remained ignorant of the events until they witnessed the first signs of flooding on the lower decks. An often asked question is what happened to the captain of the oceans – at this stage, eyewitness accounts reveal that many of the crew, including Captain Avranias, were already packed and ready to depart, seemingly unconcerned with the safety of the passengers.

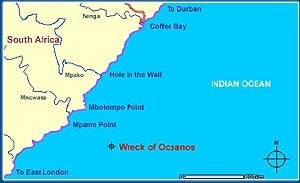

Nearby vessels responded to the ship’s SOS and were the first to assist. The South African Navy and Air Force launched a massive seven-hour mission in which 16 helicopters were used to airlift the remainder of the passengers and crew to the nearby settlements of The Haven and Hole in the Wall, about 10km south of Coffee Bay. All 571 people on board were saved, following one of the world’s most dramatic and successful rescue operations of its kind.

At about 15:30 the following day, the Oceanos could hold her head up no longer and sank. Her bow hit the sand 92m below the surface, while more than 60m of her stern remained aloft; minutes later, she was gone. She came to rest on her starboard side almost perpendicular to the coastline, with her bow facing seaward.

One week later, a 32-member team arrived on the scene as part of MNet Camera 7 news channel’s investigative documentary into the sinking of the Oceanos. Five divers, including the late Rehan Bouwer, made four attempts to reach the Oceanos, but only succeeded twice, and then only for a matter of minutes.

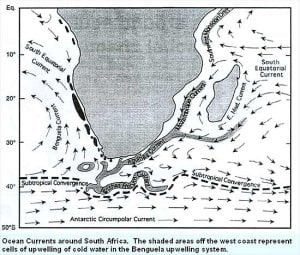

The Oceanos lies at a depth between 92m and 97m, about 5km offshore, on the western edge of the mighty Agulhas current. The Agulhas shifts an estimated volume of 70 x 106m3/s down the East Coast of South Africa, making it the most powerful current on the globe. One of the divers, Karl van der Merwe, commented, “The current was so strong that it would rip your mask off your face and your regulator out of your mouth. On one occasion the 200-liter drum we used as a marker buoy was pulled down to 34m by the current. I wouldn’t recommend this wreck to anyone but the best technical divers who really know what they’re doing.”

Unable to spend sufficient time on the wreck, the Camera 7 team was forced to deploy a remote, surface-controlled camera to acquire the footage required for their investigation.

Four months later, on December 23, Rehan Bouwer, Steve Minne, Johan Swart, Ian Symington, and Nicko Brand returned to the Oceanos. As in August, throughout the two-week period of the expedition, they only managed to reach the wreck on two occasions with a maximum bottom time of eight minutes. Steve Minne and Johan Swart confirmed the formidable force of the current. Steve said, “We had to hold onto the anchor line with all our strength. Sometimes we were almost horizontal going down. We were crazy to do that dive.”

Since the year of her sinking, the Oceanos has remained in solitary confinement, guarded by the Agulhas current and the secluded landscape of the Transkei. Then, about two years ago, South African technical divers Barry Coleman and Brett Hawton decided it was time to revisit the Oceanos.

This is their story of diving the wreck of the Oceanos

For many years, seasoned technical diver, Barry Coleman, has had one consuming desire: to dive the Oceanos. “All considered,” said Canadian-American fellow team member and cave diving world record holder Paul Heinerth, “the Oceanos is probably one of the most, if not the most difficult wreck in the world to dive.” The difficulties of diving on the Oceanos are extreme, but with commitment and proper planning, the dive is not impossible. The objective was to show how the application of experience and established diving technique to a near-insurmountable challenge could safely lead to success.

The expedition required diligent and intense preparation. A wide range of diverse considerations had to be taken care of, both personally and as a team. Physical and psychological training, descent strategies, bottom times, gas mixes, decompression profiles, equipment, and logistical planning; all these considerations had to be finalized before the team arrived on location at the Hole in the Wall hotel, where supportive technical diving and medical infrastructures do not exist.

The onsite expedition requirements included everything from personal diving gear, three imported Silent Submersion scooters, twenty staged decompression cylinders, a specialized mixed gas compressor unit, several large oxygen, and helium cylinders, three 7.3m rigid hull inflatable boats, an evacuation helicopter, and trained medical personnel.

Once complete, the team focused on preparing for the dives. The first meet was a pool session where, for the first time in an underwater environment, the divers had a chance to meet all the team members and familiarize themselves with each other’s equipment. After that, three preparative dives were conducted, including a complete simulation dive on the Griqualand, which lies at 50m, where gas exchanges and emergency procedures were rehearsed. Although Barry, Paul, and Brett would dive to the Oceanos as a team, they were all on different equipment. Barry and Paul were on closed-circuit rebreathers, a Buddy Inspiration rebreather, and a CIS-Lunar MK5P rebreather, respectively. Brett was on twin set 36-litre open circuit back-gas, with two 12-liter side-mounted cylinders.

The function of a rebreather is to re-circulate the unused oxygen in the exhaled breath whilst scrubbing it of all traces of carbon dioxide. Should oxygen levels drop below those required by the diver, O2 can be computationally or manually injected into the system from an onboard cylinder to replenish the supply. The technology means that the rebreather diver uses significantly less gas, has reduced nitrogen uptake, and subsequently fewer decompression requirements. On open-circuit scuba, the exhaled breath is not fed back into the system but is expelled and is no longer useable. The open-circuit diver is therefore restricted in terms of profile and dive time due to the chosen static supply of gas content and quantity carried.

Creating equal decompression profiles for the two systems was a difficult task for Barry that took many hours of calculation. Both he and Paul had to carry stage cylinders for Brett that would be required at specific depths, so the team had to remain together throughout the dive. Once the profiles were eventually worked out, all preparations were complete; it was time for the real thing.

The team’s arrival at Hole in the Wall on Saturday, May 3, was scheduled to coincide with a window period in which there is a reduction in the force of the Agulhas current. This window period, although based on unscientific information provided by maritime vessels in the area, falls in May and December. Various factors affect the flow rate of the current including pressure systems, the position of flow, coastal-trapped waves, and wind. On Sunday, the day before the first dive attempt, the gusty southwesterly wind blew. The current, too, was very strong, and the team was worried. Whilst laying the anchor line on the Oceanos that day, the boats remained almost stationary as the opposing forces of wind and current battled against each other for ascendancy.

Monday, May 5

The day of the first dive had dawned. The wind was still blowing, and large swells were visible on the horizon. The good news was that the current had weakened substantially, so the dive was postponed in the hope that conditions would improve later in the day. Making the most of the break, the team took some time out from the daily diving routine to explore the remarkable area with its beautiful landscapes and majestic sea views. All the while, the wind and swell were steadily dropping and, at 12:30, the decision to dive was made. Barry Coleman was yelling, “It’s a good day to dive, I can feel it in my bones!” Well, a good day it certainly was! When the team arrived at the wreck marker buoys, it was evident that the current was almost non-existent and the wind and swell had all but disappeared.

The divers descended the anchor line and were able to return to it some twenty minutes later, after making their way around most of this 152 m wreck. Attaining a maximum depth of 86.4m, the three divers initially made their way North to the stern, where Brett Hawton had time to pose next to the raised Greek lettering, spelling out the name OKEANOZ. Moving round to the port side propeller, over the hull, and back to the deck amidships, they headed off on their scooters to the bridge and bow sections to make a survey of possible penetration points for the second dive. The bridge section, however, appeared to have collapsed, leaving a field of debris on the sand below. Moving toward the bow, bad visibility and a substantially more damaged part of the wreck greeted the divers. It is this forward section of the wreck that incurred the wrath of the ocean floor as the bow slammed into the seabed. Having reached the limit of Brett’s safe air supply and time underwater, the divers returned to the anchor line to begin their ascent. Gas exchanges with backup divers at set points during the ascent worked flawlessly, and the divers surfaced on schedule without incident. All three divers were ecstatic and eager to make the most of the prevailing conditions; the second dive was scheduled for the following day.

Unfortunately, conditions did not live up to expectations. The helicopter was used to survey conditions around the wreck that lies at a distance of 9.5km from Hole in the Wall. Although conditions looked very good for diving, a large shore break was preventing our launch, and the skippers felt the risk to the team, and their vessels were too great. The dive was aborted for the day.

The weather forecast was predicting a strong northeasterly wind by morning, a factor that could easily mean the end of the expedition. Blowing in the same direction as the current, a strong northeasterly wind would slowly increase the rate of flow beyond that conducive for diving. Concern showed on everyone’s faces, but although an immense amount of planning, effort, and money is poured into conducting a deep-diving expedition, the safety of those involved is always the priority. The team retired for the night, hoping that conditions would improve.

Wednesday, May 7

This day turned out much better than expected. Chopper pilot, Ian Osborne, lifted his Alouette helicopter into the air en route to the wreck site. In a matter of minutes, the occupants returned with a very favorable report on conditions. The current on the surface was running reverse, and there was no sign of the dreaded Northeaster. Diesel, emanating from the wreck for nearly 12 years, was visible around the marker buoy – an indication that the entire water column lay still.

The team rushed to kit up and made their way to the launch site, eager to climb through the open window of opportunity while it lasted. Arriving at the dive site, the team was amazed by the conditions. It was as if the Wild Coast had been tranquilized by a hunter’s dart.

Barry, Brett, and Paul disappeared below the surface. The remaining members of the team waited on the boat; some recalled the video footage they had seen of the previous dive made on Monday afternoon and tried to imagine themselves being down there on the wreck with them. Bubbles moved toward the stern and then back again to amidships. For a moment, they disappeared – where had the bubbles gone? Then 15 minutes later, the bubbles returned, and there was a sigh of relief. The divers had penetrated 70m into the wreck with the aid of the scooters. After twenty-seven minutes at 90m and thirty-four minutes on run time, an orange submersible marker buoy broke the surface, and the deep-water back divers bailed into the water. Technical diving is an exact science, and every member of the team performed their tasks with efficiency and focus. They understood their roles and contributed to the success of this dive. Although only three divers made it to the wreck, it was the role of each team member that made it possible. On schedule, the shallow-water backup team left the boat and descended toward the decompressing divers. After the required decompression runtimes, the divers surfaced, and the team returned to shore.

Barry Coleman and the team have accomplished is an amazing feat – they have succeeded in conducting two fully controlled dives on the Oceanos. Brett and Paul penetrated the portside corridor behind the on-deck pool while Barry singularly explored the large dining hall area. Video footage shows their progress as pale rays of sunlight filtered through the corridor windows, throwing subtle illuminations across the dark interior.

Being one of the world’s most difficult wrecks to reach and successfully dive, the Oceanos offers great rewards for technical divers at the top of their game.

May she rest in peace and be as kind to those that follow this great accomplishment.

Comments are closed.