Guy Stevens is the Chief Executive and Founder of The Manta Trust, an organization dedicated to coordinating global mobulid research and conservation efforts to ensure a sustainable future for manta rays and their relatives in healthy marine ecosystems. The Manta Trust works closely with governments, communities, and stakeholders to establish long-term initiatives, drive policy change on local and global levels, introduce protective measures and raise awareness for the conservation of mobulids (manta and devil rays).

One of the top experts on these species, Guy began his manta research in the Maldives and in 2005 founded the Maldivian Manta Ray Project (MMRP) where they have identified over 5,000 individual manta rays. In 2011, he formed The Manta Trust to operate on a global scale with collaborative partners and projects worldwide. The Manta Trust’s work has resulted in national and international protections for the species and the creation of several Marine Protected Areas.

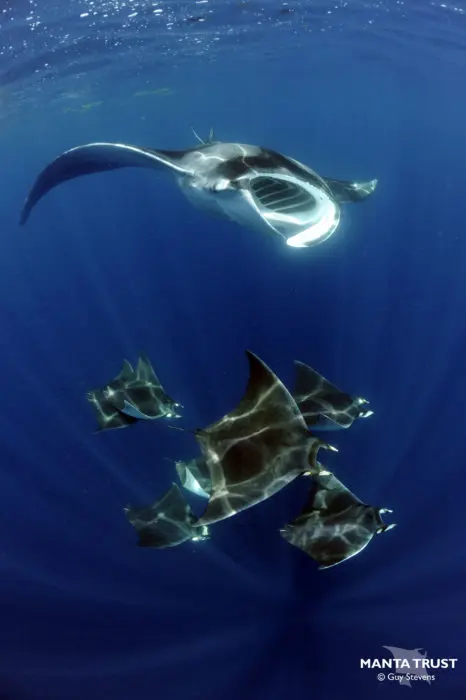

Manta rays are beautiful, social, fascinating creatures. Filter-feeders, with the largest brain of all fish, are exceptionally intelligent and curious. They are among the largest species in the oceans, but their slow population growth, combined with targeted and bycatch fisheries, makes them extremely vulnerable. As such, they have become some of the most threatened fish.

I sat down with Guy in Isla Mujeres, Mexico to discuss the emblematic manta ray, some of their imminent threats, and The Manta Trust’s vital role in manta conservation.

DeeperBlue.com: Please introduce this species. What are manta rays and why are they so vulnerable?

Guy Stevens: Manta rays are fish, and they are in the same group as all of the sharks and other rays. They’re cartilaginous elasmobranchs. There are about 1,400-1,500 different species of sharks and rays, and like most of their relatives they are particularly vulnerable because of their conservative life history, which means that they are generally long-lived, slow to reach maturity, and when they are mature, they reproduce infrequently. Those are the characteristics of their lives that tend to make them more vulnerable when they are targeted through fisheries or other anthropogenic threats.

DB: Currently listed as “Vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List, what current protections do they have?

GS: They are protected nationally and by a dozen different countries throughout their range, and they also receive international protections through various legislative frameworks like the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) or the Convention of Migratory Species (CMS), and there are a few other regional conventions as well that give them a certain level of protection. Those are the main international treaties that regulate them through trade nationally, and also Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) as some of those are really huge, encompassing quite large manta habitats as well.

DB: What are the biggest threats to manta ray populations and their habitat?

GS: The obvious one and I think probably the most accurate, would be to say targeted fisheries in which mantas are being targeted directly and fished for their meat but more often for their gill plates which are utilized in Asian medicines. This has driven fisheries in many parts of their range especially the Indian Ocean, parts of the Pacific, to a lesser extent in the Eastern Pacific or the Atlantic but certainly, fisheries still occur for them there. In those instances, fisheries tend to be more driven by the demand for the meat, which is low quality, consumed locally, dreadfully, but still considered valuable enough to drive fisheries.

And then of course bycatch as well in larger fisheries on the high seas that are generally targeting other species like tunas, etc. Bycatch is certainly a big concern.

More of a less quantifiable but still really serious concern is the impact of climate breakdown. We are going through changes on this planet that humans have never faced before, and species that are alive today mostly haven’t evolved to be able to deal with this level of change that we are exposing them to. Manta rays like all species on this planet are going to have to adapt to this rapidly changing world of ours. And how they are going to adapt, if they are able to adapt, especially coupled with the other threats that they are facing, is very much an unknown. That’s one of my biggest concerns because even if you can protect them from these short-termed targeted fisheries or bycatch fisheries or the negative impacts of development, degradation, and so on, what’s going to happen if the oceans stop producing any food because we mess up the circulatory system? That of course is not just a doomsday scenario for the mantas, but for all of us because that’s a big concern. That’s a really really big question.

DB: Tourism is also a factor

GS: Yeah, it’s definitely one of the lesser of the evils, but certainly not one that you can ignore. Tourism certainly needs to be managed, regulated, and considered when trying to implement management, conservation measures.

DB: What are your thoughts on introducing manta tourism to Isla Mujeres, Mexico?

GS: I think it’s inevitable. I think it’s good. I think it is a better way of utilizing the resources that the islanders have so that the local economy can benefit. However, as with all tourism with megafauna in the oceans, there is a balance that you need to strike between the rewards and the impact.

The advantage that we have here is the opportunity of knowing how tourism can lead to negative impacts on manta populations around the world. We can put in place safeguards and proper management plans before tourism even begins. In most places, tourism happens naturally and begins to occur where mantas are seen as an opportunity for diving and tourism operators. Here that hasn’t happened yet, which is surprising in a way. It’s a good opportunity to get it right, or more right, upfront from the beginning.

DB: As opposed to having to backtrack and change people’s ways of doing things.

GS: Yeah, exactly. It’s very hard to retroactively or retrospectively try to make changes because there is always pushback. Because change generally reduces the freedoms of the operators and that is perceived as reducing their revenue opportunities. So if you don’t have to go through that process, then it makes it a lot easier.

DB: There is a lot to consider when protecting a species. What is The Manta Trust’s approach to conservation?

GS: There is no golden bullet, there is no easy answer. You have to work from the top-down and the bottom-up. You have to work with all the stakeholders. We have set out quite a comprehensive plan, a strategy for conservation for this species. It’s not just mantas but the whole family as well.

We have tried to break down all of the threats and compartmentalize them, and then to seek out ways of addressing each of those; how we are going to do that and what are the financial implications for the lifetime scales for that, and who we are going to work with to try to get that done. With that plan in place, with all of our partners around the world, we say “All right, who is going to tackle this in this area and how can we help you do that and what money do we need to do it, etc.”

It’s a pretty simple process in vision; the hard work becomes when you start trying to actually make things happen. We have been pretty successful to date, I think. I think that’s mainly been a result of trying to collaborate as much as possible and to work with as many people as you can to try to get buy-in from governments and communities, and so on. You can’t just go in somewhere and say “Hey, this is what we are going to do. This is what we need to do.” It’s better if the ideas come from within the local communities and you can guide them and help a little bit.

DB: So there are many hurdles for getting protection for manta rays; awareness, dealing with governments, implementing regulation …

GS: Yes, all of those. Some of those are more of a priority. Generally, you can simplify like this: If mantas are worth economically more alive than dead in a country, for example, dive tourism, then you have more of an incentive to push governments to be proactive economically. In other words, you can say “Look, you can protect these animals because they are worth more alive, and therefore that is a good approach to being successful.” In areas where there is no manta tourism, then you have to approach things differently and that will affect your strategy and your approach.

DB: What issues do you think need to be addressed next?

GS: The big one we are trying to figure out at the moment is the impact of these bycatch fisheries in the high seas. We have a pretty good handle on the targeted fisheries in those countries that are catching mantas or mobulas for meat or to supply the gill plate trade. We know that these practices where direct or targeted fisheries have occurred have led to population declines, big declines in some cases. The problem we’ve got now is, what’s left out there? How many individuals are in these populations? If we know roughly how many are being killed in these targeted fisheries, and if we can start to quantify how many are dying as bycatch, we can then apply that to our population estimates, and then we can start to figure out how threatened they are, or how quickly these populations and potentially species can even go extinct. And that is really where we are trying to put our research focus at the moment: quantify bycatch fisheries and quantify the population size of the various species in the various ocean bases where they occur.

DB: If you could suggest one thing to change in our daily lives that would make a difference for manta rays, what would you advise?

GS: Change your diet and think about the way you eat. Eat less fish if you can. And if you are going to eat fish, try to eat sustainably. For example, 20-30 years ago, everyone became very much aware of the impact of tuna on certain dolphin species that were caught as bycatch. And I think most people now notice when they pick up a can of tuna or most of the companies that sell tuna go to great lengths to put on their tins “dolphin friendly.” Now that doesn’t say “manta friendly” or “turtle-friendly” or “devil ray friendly,” because these fisheries are still killing as bycatch a lot of these other species in the oceans. If you care about mantas and want to do something to help them, buy tuna that specify pole and line caught. Anything that is caught in a net in the oceans is going to have bycatch associated with it. Therefore, you can think about net fishing as generally the worst type of fishing, obviously there are other bad fishing techniques like long lines, but generally, nets especially drift nets and gill nets and purse seine nets. These are huge nets that are used to fish huge quantities of animals from the oceans. These are not like little nets that you usually envision when you think of fishing nets. These are things you can fit like 20 jumbo jets in the mouth of. These are huge, they encircle massive stretches of the ocean and catch everything that’s in it including mantas and in many cases devil rays and lots of other animals too like whale sharks.

Eat more sustainable seafood or ideally go vegetarian. If you are really going for it, go vegan. The world needs to go vegetarian. If there’s a single biggest thing that the world needs to do, it’s – stop eating meat. The best way to tackle climate breakdown is to go vegetarian.

DB: That’s powerful advice. Can you share a memorable moment with a manta ray and why they are such beautiful creatures that we need to protect?

GS: Yeah, it’s a question I get asked a lot. Why mantas? Why should we care?

The easiest answer is not to use words, but to put the person in the ocean. It’s not so easy to do that which is why I often fight for the cause for aquariums cause they have a strong ability to engage and influence people who are unable to go into the oceans like we are. And also increasing the things like VR technology like you put a VR headset on someone and immerse them in a school of manta rays. That also has a strong impact on them.

However, if I were to put it into words, they are truly grateful, beautiful animals that you never feel fearful of when you are in the water with them. There are very few animals that will approach you that closely that are that big. To be in the ocean with such a huge wild animal, and have it swim up to you within inches, check you out, stare in your eye, and have it think about you just as much as you are thinking about it is a really emotive experience and one that you can’t help but be moved by. It’s something that will leave a lasting impression on you. For me, I always feel that way when I am in the water with manta rays, and there have been hundreds of amazing encounters.

One encounter that always springs to mind, I’ve rescued many, but there is one particular animal that I was able to cut free from a fishing line that really left a lasting impact on me because it was the first animal that I properly was able to cut free from the line. It was so badly injured that it clearly couldn’t even open its mouth to feed. It was trying to feed but was swimming around wrapped up by this line and it was cut so far down into its head, because the line is like cheese wire, so as soon as the animal moves its mouth to open it or as it flaps its pectoral fins up and down, it’s like a knife that cuts deeper and deeper. It had these horrific wounds and it couldn’t free itself and I was able to cut it free. As many people will have seen, if you go on YouTube and search “Manta Rescue,” you’ll see dozens of these accounts, of these animals soliciting people’s help. Clearly asking for help. And this animal was just like that. He came up to me and just hovered and waited for me like pleading with me to help it. There are very few wild animals that will allow you to do that. If you similarly are in ocean rescue with whales or other animals, they are usually thrashing around, they are scared, they are trying to escape because they are fearful of the person that is obviously trying to help them. But manta rays somehow seem to know that people can help them. This is not just a one-off. It’s happened to me half a dozen or so times, it’s happened to dozens of other people. To have this animal ask you for help, to be able to then help it, and then to afterward see it clearly continue to engage with you as if to say “thank you, who are you, why did you do that, but I appreciate that” is something that you can never forget.

DB: Amazing. What’s your biggest motivator?

GS: My motivation comes from a desire to try and do something positive in this world. I have a job that I love. I am blessed to do something that I don’t really think about as “work” for a living. Obviously, the oceans and planet are not getting any more protected or any better for the animals. So every day there is more need to work harder to protect what is left of our natural biodiversity. It’s really sad because I can see the declines and the changes even in the couple of decades that I have been venturing to the oceans. Things weren’t good when I started, and they certainly haven’t gotten any better. The ocean is in trouble. The manta rays are in trouble. That’s what drives me – the need to make everyone aware of the problems. Ultimately things will only change if people care, if there is a desire to protect these animals, and most of that change needs to come from the government. There needs to be a fundamental shift in the way we value everything in our lives. Everything, at the moment, is valued economically with a dollar sign and we don’t value community, we don’t value our natural resources in the way that we should and as a result, those things are not protected. We need a complete restructuring of society instead of chasing immaterial wealth and a desire to have these continuously expanding economies, which don’t work for anyone except the 1% of the world at the top, when the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer, and we are screwing up the world in the process. We are reaching a point where that isn’t going to work for much longer. We need to think about what we want to be doing in the next 20-30 years cause if we don’t change it soon, it’s going to end in a very dark place.

Mantas are an emblem of what’s at stake. Imagine a world in 20-30-50 years’ time with no mantas. That would be sad, and I think a lot of people would agree. If you can use these charismatic, emblematic species as a way to shake people up a little bit and say “Look, this is what we stand to lose”, I think that is a motivator for engaging, and then people’s engagement will lead their voice to push the government to make a difference. That’s not to say that mantas are more important than say a clownfish or a nematode worm, but from a change-making perspective they are more important, I think because humans don’t value things equally when it comes to biological life. Obviously, I am biased since mantas are amazing.

For more information, you can follow The Manta Trust on Instagram: @MantaTrust or visit their website www.MantaTrust.org